Immersive experience and preservation: The Sosoro Museum perspective

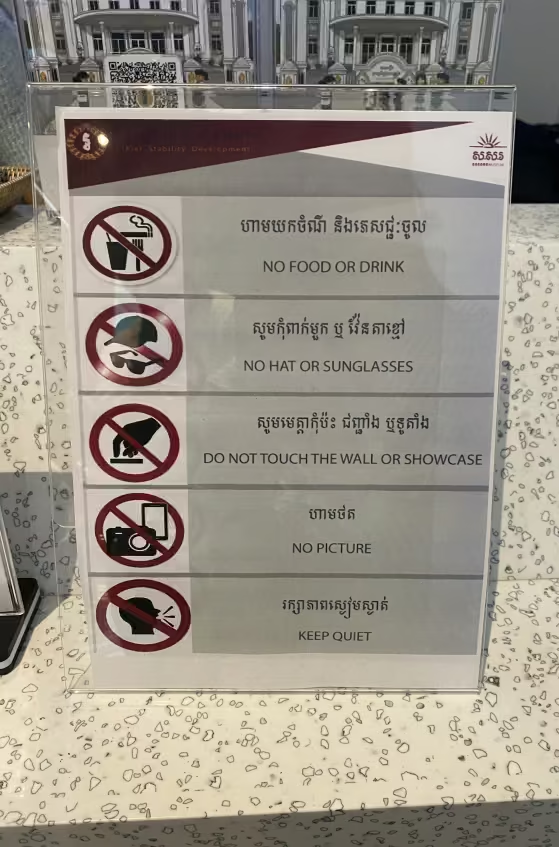

The SOSORO Museum, dedicated to Cambodian economics and finance, justifies its ban by citing its desire to maintain a smooth and immersive experience for all visitors. The argument is clear: allowing photography can quickly lead to congestion, distractions, and disrupt the flow of the visit for other guests. It's easy to imagine the queues in front of a work of art, the untimely flashes, or groups waiting around for the perfect shot.

This is why the museum strictly regulates this practice: during group visits, only one identified person is allowed to take photos, in order to limit inconvenience while allowing for a certain degree of flexibility.

In addition, the museum highlights a potential risk to the objects on display. While flash photography is known to have a harmful effect on pigments and fragile materials, even constant ambient light or crowd movement can, over time, contribute to the deterioration of objects. The aim is therefore to ensure both visitor comfort and the long-term preservation of the collections.

This is why the museum strictly regulates this practice: during group visits, only one identified person is allowed to take photos, in order to limit inconvenience while allowing for a certain degree of flexibility.

In addition, the museum highlights a potential risk to the objects on display. While flash photography is known to have a harmful effect on pigments and fragile materials, even constant ambient light or crowd movement can, over time, contribute to the deterioration of objects. The aim is therefore to ensure both visitor comfort and the long-term preservation of the collections.

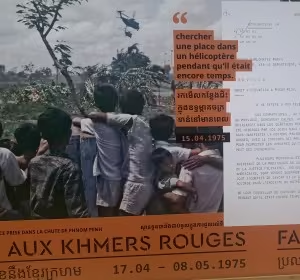

Dignity, authenticity, and the fight against misinformation: The case of Tuol Sleng

The museum wishes to limit the risk of images of the site being shared with incorrect explanations or inappropriate comments, which could distort the historical message and disrespect the memory of those who have passed away. In a place of contemplation and remembrance, silent reflection and respect take priority over taking pictures.

The National Museum: Silence and apparent inconsistency

Surprisingly, the national museum did not respond to the request regarding its photography policy.

This situation raises questions, especially since the National Museum recently made an exceptional loan of 126 pieces to the Guimet Museum in Paris for the exhibition “Royal Bronzes of Angkor, an Art of the Divine” until September 8. The Guimet Museum, like most French museums, generally allows visitors to take photographs (without flash). This apparent inconsistency—lending works to an institution that allows photography while prohibiting it at home—raises questions about the overall strategy and underlying reasons for this restriction in Cambodia. Is it a matter of copyright, crowd management, or some other undisclosed consideration?

This situation raises questions, especially since the National Museum recently made an exceptional loan of 126 pieces to the Guimet Museum in Paris for the exhibition “Royal Bronzes of Angkor, an Art of the Divine” until September 8. The Guimet Museum, like most French museums, generally allows visitors to take photographs (without flash). This apparent inconsistency—lending works to an institution that allows photography while prohibiting it at home—raises questions about the overall strategy and underlying reasons for this restriction in Cambodia. Is it a matter of copyright, crowd management, or some other undisclosed consideration?

And elsewhere in the world?

In many Western museums (the Louvre in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the British Museum in London, etc.), flash-free photography is generally permitted for personal use, with visitors even being encouraged to share their experiences on social media. The idea is that this generates engagement and promotion and makes art more accessible.

The policy of prohibiting photography in Cambodian museums, although sometimes justified by valid reasons such as the preservation of works or the dignity of the place, raises questions. In an increasingly connected world where images are a powerful vehicle for sharing and promoting culture, this approach may seem counterintuitive.

The contrast with the Paris exhibition is striking: on the one hand, freedom that contributes to success and influence; on the other, restrictions that can slow down public engagement and the diffusion of heritage.